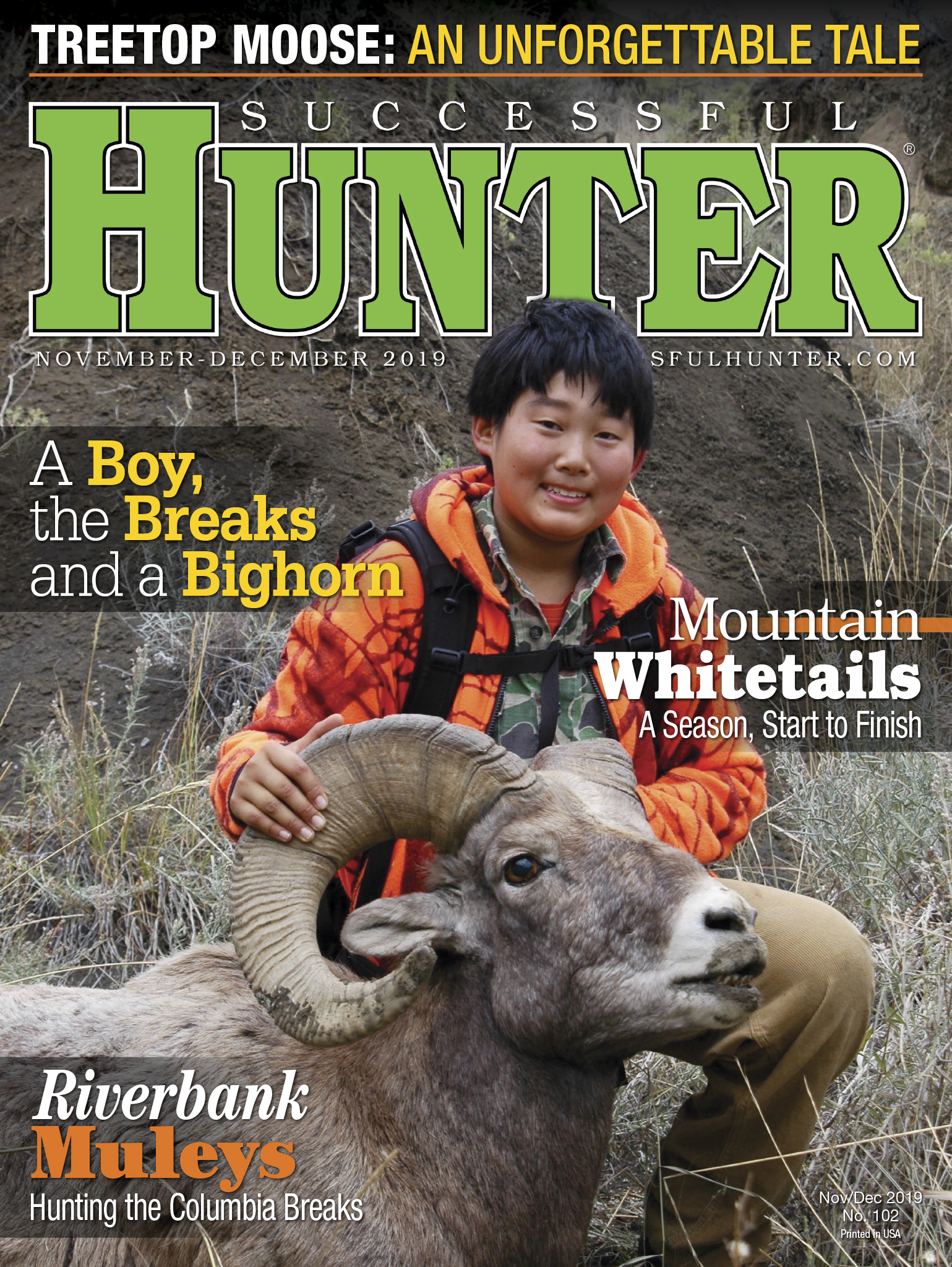

Riverbank Muleys

Hunting the Columbia Breaks

feature By: Jason Brooks | November, 19

The area we were hunting was public land surrounded by private holdings, making it an “island” of refuge for the deer. Steep canyon walls reached up toward the plateau, and at the bottom was the river. Along large benches of sediment deposited thousands of years ago are several apple orchards. Apple orchards are great for deer as the tall summer grasses and frequent water spraying from sprinklers means cool evenings during the hot months. As fall comes near the apples sweeten and the deer aren’t shy about their sweet tooth. But the activity of fall harvest chases the deer out of the orchards and into the arid lands above, where sage brush grows tall and offers shade and protection.

At the top of the gorge are the flatlands of the Palouse with rich, fertile soil that grows wheat. The “Great Flood” carried silt deposits from the immense Rockies of central Idaho and Montana as a large lake formed in eastern Washington. This region holds vast tracts of private land and plenty of feed for the mule deer that live here. Predators are mostly coyotes, as the deer thrive in wide open country with very little food for black bears and no cover for mountain lions. Central Washington is not often thought of as a “trophy” area, mostly because the deer don’t sport record book antlers and the hunting season is short, just nine days in mid-October.

It was opening morning of deer season when Chad and I found ourselves parked at the edge of the orchard. We knew we had to climb up the steep canyon walls and the afternoon sun would warm the cool air along the river and winds would come upward in a thermal, carrying our scent up to the bedded mule deer. The morning hunt would be our best chance, as the deer wouldn’t be able to smell us and we could gain enough elevation to get within shooting distance before the warm afternoon winds started.

Parking at the edge of an orchard, the headlights illuminated the first rows of trees, saplings in a newly planted orchard. Three or four of these small trees had been reduced to wood shavings and lacked any branches. A buck had made quick work of them while stripping its velvet a few weeks earlier and destroying the trees. Now I understood why the orchardist was excited when he offered us access to the edge of the orchard and the slopes above.

The three deer we first spotted at daylight fed over the ridge and continued upslope. So we did the same and hiked farther up. Finally coming to a small plateau and a place to glass across a steep canyon, two more deer were spotted, both bucks. Using his pack for a rest, Chad picked out one of the bucks across the canyon. It would be a long shot, but luckily the thermal winds hadn’t started, so he made an educated guess on holdover and didn’t worry about crosswind. The buck jumped at the shot and then stumbled before it fell and rolled down into the ravine.

A flat-shooting rifle is preferred by hunters in this region. Chad shoulders a .270 Winchester and I had my 7mm Remington Magnum. Shots on the open slopes can be several hundred yards but once you make it to the benches above, the stalking game begins. Tall sage allows a hunter to close the distance, but it also allows for concealment and the deer often jump up right in front of the hunter.

Mule deer are known for their “stotting,” a high-jumping run where they spring on all four hoofs at the same time. They can cover distance quickly, but the main reason why they use this mode of escape is so they can

Looking for a second deer, a white patch was spotted dodging between tall sage over the crest of the hill. Knowing the buck was still above us and had nowhere to go, we made our way to Chad’s deer. Piled up against a tall sage, the deer was folded over and held from any further tumbling toward the river bottom. It wasn’t a big buck by any means, but it had more than the required three points on a side per Washington’s mule deer regulations.

Neither Chad nor I are “trophy” hunters, and through the years we have taken a fair share of mature muley bucks but never passed on a legal buck, especially one that has been feeding on apples. After helping to get the buck into a position to be field dressed, I decided to hike up after the other deer.

It was a slow climb as the canyon walls steepen the farther you get from the river. Hundreds of years of erosion have washed any of the fertile Palouse soil down to the streambed of the river, exposing basalt cliffs and large slopes of shale slides. A fall would mean broken bones and torn skin as you tumble toward the flowing water several hundred feet below. Thankfully, the land has eroded to form several benches, much like a cascade of rocks and sage lands. I knew that the buck would be up on the next bench because it didn’t know where the shot came from

An hour after Chad had taken his buck, I finally made it to the bench. Creeping over the last few feet, the terrain leveled out and the sage hills turned into brush that was as tall as I was. A doe and fawn were only 30 yards away and feeding. Then the buck’s antlers appeared on the other side of the sagebrush. It had made it to the bench and fed in the early morning sunshine.

Luckily, that buck hadn’t bedded down yet. It’s easy to walk right past deer in the thick brush. Taking a few steps around the sage the buck looked up as I stood, holding my rifle in an offhand shooting stance and finished my hunt. This buck was the same age class and size as Chad’s and would make the orchardist happy to have it gone so it would no longer tear up any more apple trees.

After field dressing the buck, I began the tedious task of dragging it down the hillside. Often the buck would slide and pull me with it, but I made sure to keep it from rolling and bruising. Halfway down the slope I met back up with Chad, who was enjoying the view and having lunch. Neither of us where in a hurry to lose the elevation we had gained in the early morning light. The mid-day thermals blew and cooled us as we pulled on our deer. Once back at the truck, the bucks were loaded up and we slowly drove past the workers as they put out apple bins and drove tractors. A sense of accomplishment came over us as we knew that we helped the orchardist and filled out deer tags on opening day.

More than once we have returned during the fall harvest and climbed the breaks above the Columbia River. The deer always seem to be in the sagebrush, taking refuge in the sage islands that provided cover as the thermal winds drift upward. Chad brought his daughter Marissa to the arid slopes when she had drawn an “any deer” youth permit the next fall. Taking

Sometimes the hunt lasts a week, or even to the last minute, and sometimes it ends before lunchtime on the first day of the season. Either way, hunting along the breaks of the Columbia River holds special relevance for those that climb up the basalt cliffs to the dry lakebed of the in search of a mule deer buck.