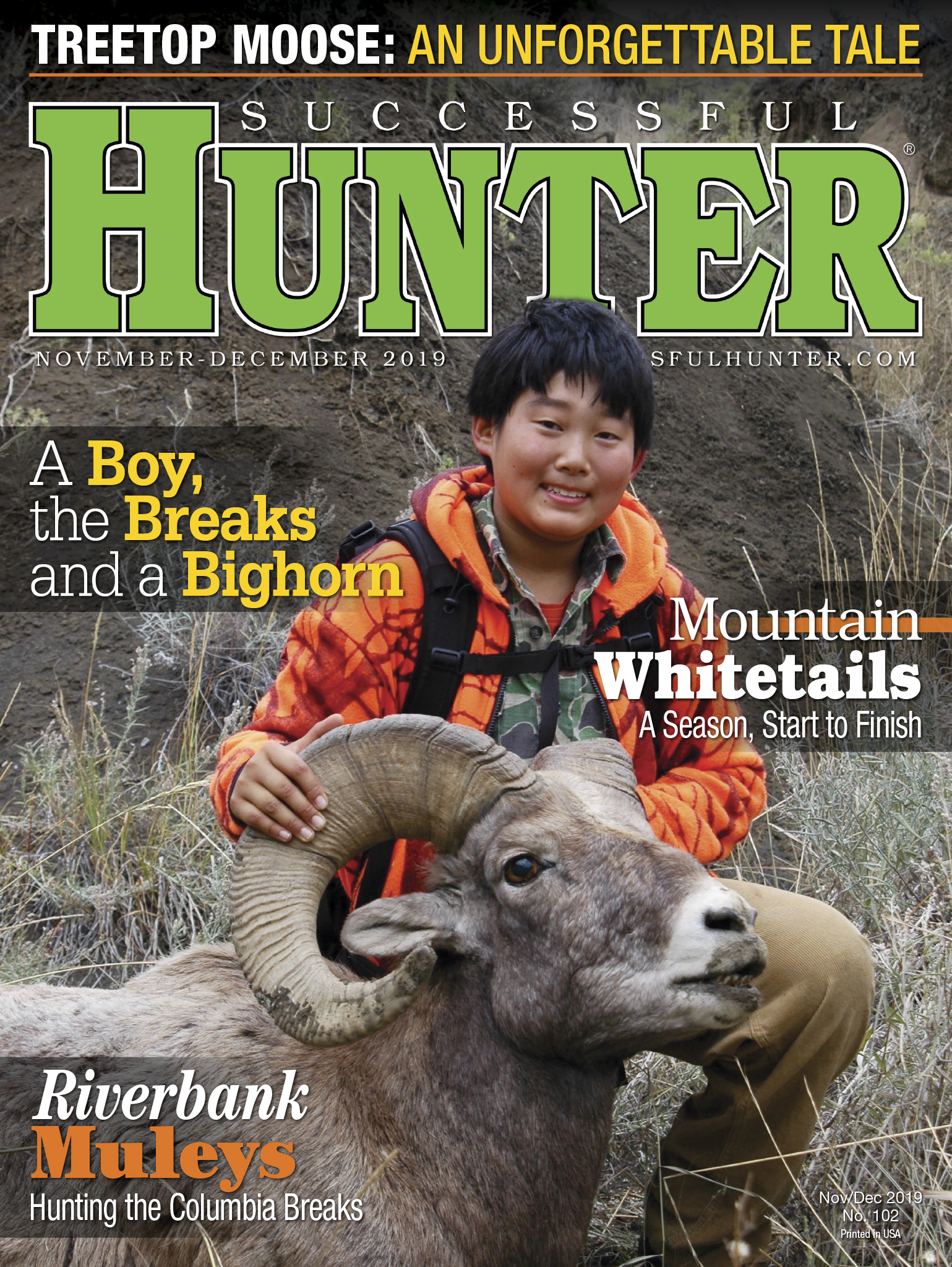

Observations

Crown Prince Coues

column By: Lee Hoots | November, 19

Hunters who tag mature animals year after year on state or federal ground on their own dime and time are certainly dedicated. Furthermore, removing older animals does not alter herd genetics, as some people still believe. In fact, it’s sound conservation. Still, it’s the largest mule deer and elk antlers that stir most hunters’ imaginations, though not all of us are so hyper-focused.

While a large set of antlers from an old bull or mule deer can get any devotee’s blood flowing, there is a small but dedicated group of woodsmen who prefer the challenges of the Southwest’s littlest deer, the Coues’ whitetail found in Arizona, Mexico and parts of western New Mexico. I can’t say one deer is preferred over another on a personal

Did I say they were little? In Deer of the Southwest, A Complete Guide to the Natural History, Biology, and Management of Southwestern Mule Deer and White-tailed Deer (2006), wildlife biologist and author Jim Heffelfinger describes the deer thusly:

“The Coues whitetail in the Southwest stands about 32 inches tall at the shoulder, which makes it one of the smallest forms of white-tailed deer… Dressed weights of Coues white-tailed bucks average…85 pounds for bucks 3.5 to 5.5 years old. Bucks over 6 years old average 93 pounds, with very few over 100 pounds… Whitetail body size increases at the eastern edge of Coues whitetail distribution.”

It’s possible these “100-pound” bucks, sometimes referred to as Arizona whitetails, fantails and other regional nicknames, receive comparatively little attention due to their size. If that’s true it’s a shame, because the small-statured cousin of the common Virginia whitetail can be as difficult to hunt as the oldest and wisest bull elk or magnum muley. In fact, a trophy Coues’ buck might be harder to find and bag.

According to Heffelfinger’s research, Coues’ deer were first recognized in the mid-1800s and were later named after Elliot Coues (a well-known naturalist who never personally collected one of the deer himself) by one Doctor Joseph Rothrock. This should set the record straight, but in my own recent research some writers still continue to perpetuate the idea that Coues himself was responsible for discovering the diminutive whitetail.

I’ve hunted Coues’ deer now and then in Mexico, but my first encounter with a stunning, large-antlered buck, a really breathtaking deer, took place long ago while bow hunting in central Arizona. One December while stalking a troop of javelina in rugged terrain a few miles east of Prescott, an 8-point buck walked into an open bowl within range of my Black Widow bow and crested arrows. Without a deer tag I stood in wonderment, quivering as the buck slowly ambled off – that will happen to a kid in his 20s.

Coues’ deer, depending on location, are generally found at mid-elevations, say roughly 6,000 to 7,000 feet, though they are known to be found much higher and sometimes much lower.

While there are “average” and “trophy” antlers on mule deer and elk, any Arizona whitetail taken in fair chase is a good buck. Any Coues’ buck should be considered a prize, but for hunters who might be interested in record scoring, the Boone and Crockett Club requires a score of 100 points for a typical buck and 105 points for a nontypical. In the same order, “All Time” qualifications require 110 and 120 points. If a hunter’s goal is to put a buck in the “book,” first look for deer with heavy beams that reach or exceed the width of the deer’s outstretched ears. Most mature bucks carry two tines off the main beams. As with all whitetail subspecies, the taller the tines, the better the score. Likewise, eye guards should be as long as possible and overall mass should be obvious.

Most Coues’ deer have typical 8-point racks but non-typicals are not uncommon. The first buck I shot in Mexico had points jutting in all directions, many of them broken or chipped. That buck was an old scrapper, no doubt. In spite of my guide suggesting it wouldn’t score well, the old buck was a sure enough trophy, and its antlers hung on the wall for years before it got knocked off and shattered.

As is true of most western big-game hunting, whether with a bow or rifle, long hours of glassing and dissecting each inch of canyon or ridge, then doing it all over again before moving to a new vantage point, is the key to finding a nice Coues’ buck. In fact, probing for long hours for dainty whitetails may be the most challenging part of hunting them – perhaps the most challenging of all deer hunting in the West. For years a Swarovski 15x binocular mounted to a lightweight tripod has served well. In fact, a good binocular or spotting scope may be more important than a high-dollar rifle; a whitetail hunter will glass for days but only shoot once, maybe twice – perhaps not at all.

Two years ago, I hunted on a large and thriving cattle ranch in Mexico with outfitter Ted Jaycox (talltine.com). By way of careful management on behalf of Jaycox and the ranch’s owner, there were bucks everywhere, along with Gould’s turkeys. Having been on Mexican ranches where shooting a decent buck proved somewhat difficult, suitable deer were seen daily on this trip; the brushy terrain, however, made getting close to a mature buck difficult. While glassing from hilltops and somewhat remote ridgelines, a hunter would need three hands to count all the bucks glimpsed. There were several hunters in camp and at night we’d sit around the fire in a very comfortable bunkhouse and share our findings with each other.

Having seen so many bucks, including record book candidates, holding out a little longer seemed like a worthwhile plan. In the meantime, another big deer with an impressive green score would show up at camp as we gathered each evening.

With two days left, my experienced young guide and I spotted “the buck” as evening came on. As old bucks tend to do, it provided only glimpses of its antlers while feeding in heavy cover. As the sun began to sink beyond a distant mountain, we slithered several hundred yards closer toward the deer.

At last the magnum 8-point stepped clear of woody cover, then bucked when the bullet hit its chest and ran out of sight toward the brush where it previously fed, a sure sign of a dead Coues’ deer. My heart sank when I walked to where it stood when shot and found only one small drop of bright-red blood. We searched carefully downhill along the buck’s path, finding another drop of bright blood. Then the sky turned black in a hurry as it does in the desert Southwest. The howling of a nearby pack of coyotes turned my guts.

The trail was picked up again at the crack of dawn, but obvious hoof prints were soon lost on hard-scrabble ground. An entire day was spent in those hills, but it turned up nothing. The following spring I got a call from Jaycox: “The cowboys found your deer while riding horseback in a canyon adjacent to where you shot, just a couple of days after you left. We’ll be done with turkey hunting in two weeks, and you can drive down from Prescott and get it. We have video of the deer you shot, and this is it!”

The largest Coues’ deer I’ve had the opportunity to see while hunting has been home for more than a year.