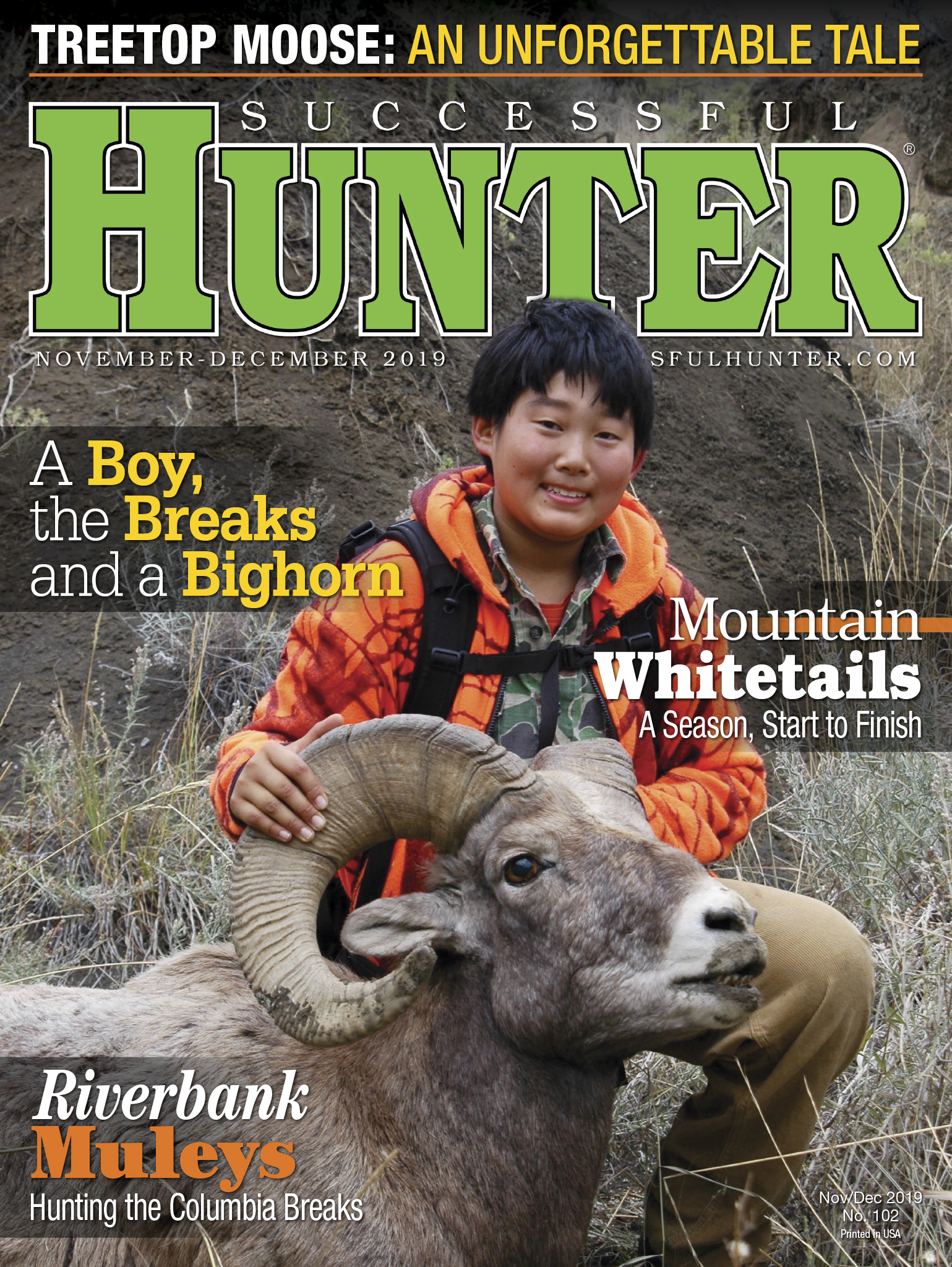

Backcountry Bound

Busted

column By: Jack Ballard | November, 19

Busted, we hoped the herd would settle and stay put. After all, it was early morning on the first day of antelope season and we were definitely the first hunters the band had encountered for the year, but the situation proved otherwise. First, the closest doe turned to face directly toward the hiding hunters. Soon the entire herd was peering at the thin screen of grass stalks and a scrawny sage behind which we’d dropped. Then came a snort-wheeze from a skittish doe. Echoes from a couple of its counterparts launched the herd into high gear, a fine buck running at the back of the band. Faster than I could sprint across a parking lot, the pronghorn reached the far side of the basin a half-mile away and disappeared over a rise.

A better approach is to take a cue from wildlife photographers. In that profession, the “frame-filling photo” is the mother-prize of all images. Attaining it often means closing the distance between the photographer and a suspicious subject to achieve the necessary magnification, even with a telephoto lens. It starts with being spotted by the subject, but rather than trying to duck and hide, the seasoned photographer remains in plain sight in a stationary position, making no attempt at concealment. This gives the subject the option to flee (it sometimes does) but also the chance to check out the situation. Especially in places like wilderness areas where animals infrequently encounter humans, the curiosity of normally wary species will outweigh their caution. They eventually accept the human interloper as benign and will allow a closer approach.

The photographer’s actions upon being spotted are often the “make or break” part of the equation. Stare directly at the subject or stealthily swivel the lens (a gigantic eye) in its direction and the most typical reaction is a heightened sense of alarm. Look away in a relaxed manner and it greatly reduces the perception of threat. Following this pattern in a hunting situation where and when animals haven’t been over-pressured may buy enough time for a shot.

In some instances, there’s no way to get into shooting range without coming into the visual field of the intended quarry. This occurs frequently in open country, where an expanse of exposed territory lies between hunter and game. I’ve been in this situation numerous times when hunting mule deer and pronghorn on the prairie, and in a few cases confronted the same challenge when hunting elk on open, south-facing slopes in the foothills.

There’s a trick that’s surprisingly effective in such situations, especially when it’s employed at a reasonable distance, say a half-mile or more from the quarry. It relies on an

Last season my wife and I found ourselves on a chunk of public land in eastern Montana, an antelope tag burning a proverbial hole in her pocket. It was a large parcel of intermingled state and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) acreage that was obviously no secret to hunters. When a herd of antelope raced off after spotting our vehicle from a mile away, I was ready to find a more promising destination. Lisa, ever the optimist, thought we should at least take a hike to look around.

We forged westward into a slight breeze. Not far into the trek, we pulled up to glass ahead at the top of a gentle rise. Twelve hundered yards away, ranged through a Swarovski binocular, was a bedded band of antelope. A low hill in front of them would screen our stalk, but we would need to cross the next 100 yards completely within the animals’ view.

“Time to play horse,” I informed Lisa.

“Huh?”

I briefly explained the procedure. We would both bend at the waist, Lisa holding on to the back of my belt, her forehead pressed into my lower back. Then we’d walk slowly ahead in plain sight, feigning the shape of a horse. We’d move at a leisurely pace, stopping here and there so I could drop my head toward the ground as if grazing.

It won’t always save the day, but a mindful attitude toward one’s reactions after being spotted by game is yet another trick in the seasoned hunter’s book. Busted doesn’t necessarily mean “game over.”