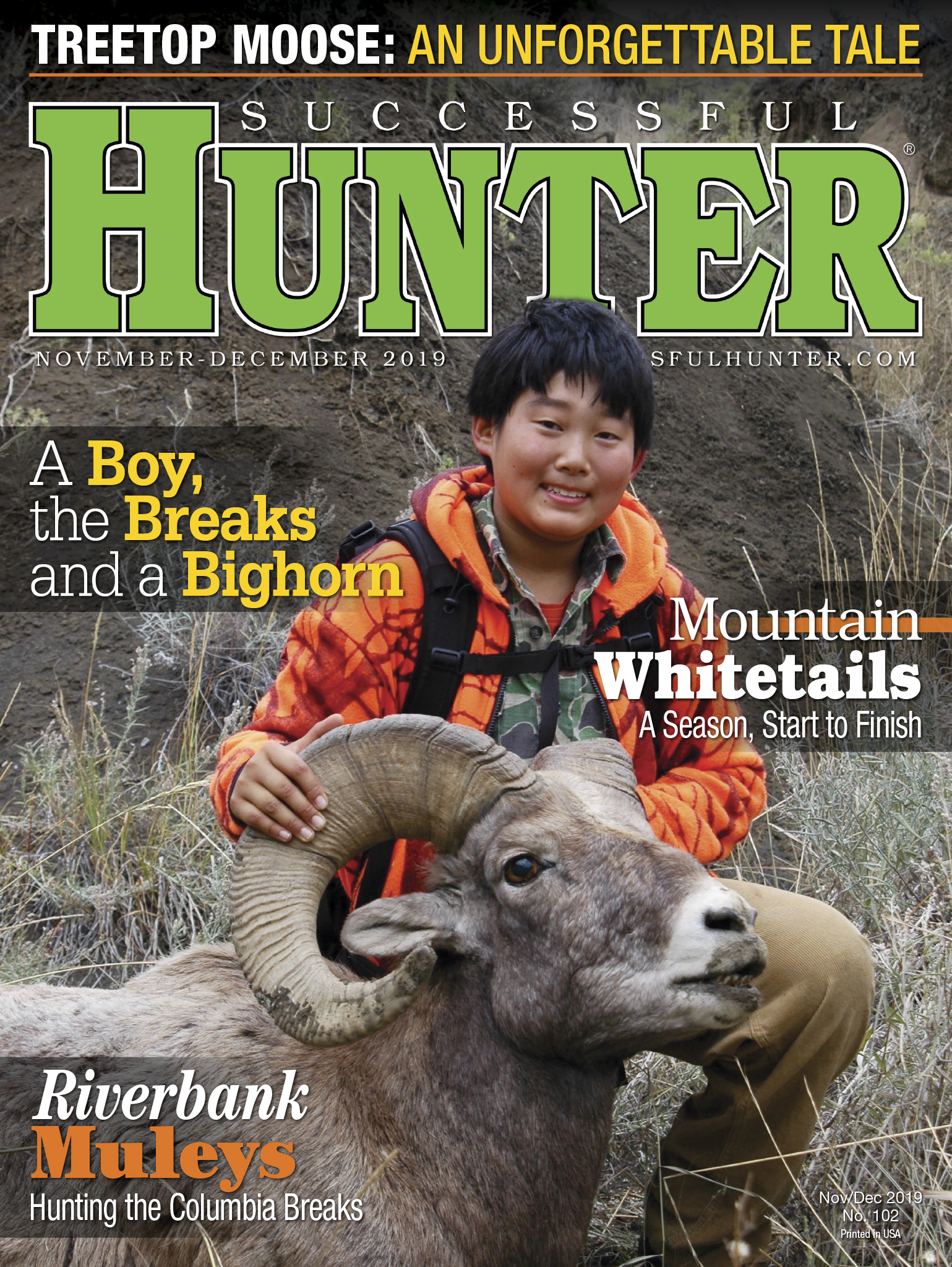

A Boy the Breaks and a Bighorn

Beating Montana's Sheep Lottery

feature By: Jack Ballard | November, 19

Among the accomplishments of the Lewis & Clark expedition, the “discovery” of more than 100 species of birds and mammals previously unknown to early scientists represented a fascinating trove of information for

On May 25, 1805, William Clark and two other hunters each killed what French explorers dubbed the “rock mountain sheep.” Members of the expedition had never seen animals like these. In their camp in the rugged breaks of the Missouri River in north-central Montana, Lewis painstakingly portrayed the creatures in one of the most complete descriptions he penned of any animal on the expedition. On the return trip down the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers the following year, each of the captains took great pains to secure specimens of this creature, returning to civilization with the heads and hides of a half-dozen animals.

Some two centuries after Clark killed his first “rock mountain sheep,” the inquisitive eyes of a brown-skinned youth scanned the Missouri Breaks in search of a bighorn ram. The teen’s desire to secure an ovis canadensis specimen was as keen as Clark’s. Although the many years separating the explorer’s hunt from the boy’s spawned momentous changes to the landscape, two facts remained. Bighorn sheep are still highly coveted by hunters and Montana’s Missouri Breaks are a sheep-hunter’s dream destination.

Four months previously, I engaged in the yearly June ritual of checking my family’s drawing status in the Montana lottery for sheep tags. Punching in my identification, I read “unsuccessful,” the same result in over 30 years of applying. Next, I checked my oldest son, Micah. When “successful” flashed onto the screen I nearly fainted, then cussed myself, assuming I’d accidentally placed him in the drawing for a ewe tag. But, no, he had miraculously beaten the one in 1,000 odds to pull an either-sex bighorn tag on his second try.

Despite our excitement about the tag, logistics posed problems. Scheduling a hunt that meshed with his schooling became a challenge in chasing a ram. He had a two-day vacation in mid-September, shortly after the season opened, but the Sunday beforehand his uncle passed away. A funeral in Denver took priority over the hunt.

Five weeks later, we finally got our chance. Leaving on Friday afternoon after school we reached his hunting area after dark, pitching a tent amidst the prickly pear and sagebrush. What seemed less than an hour later, the alarm chirped six inches from my ear. The eyes of a kid who normally needed a stick of dynamite to roll out on school days snapped open with excitement.

“Time to go, Dad?”

“Yep,” I said.

I watched in amazement as he quickly pulled on his clothes and readied his pack. Sheep hunting appeared infinitely more motivating than pre-algebra. Twenty minutes later, after a bowl of cold cereal and milk, we wove

From the top of a grassy butte, the sunrise spread across a landscape bearing the appearance of the excavations of a cosmic gardener hacking the earth with a supernatural spade. Twisted coulees and deep ravines, their sides serrated with sandstone outcroppings, descended from the uplifted prairie behind us to the Missouri River, now impounded by the Fort Peck Dam many miles downstream. The sun’s rays inflamed the flinty earth, burned in hues from the color of a bleached wheat-stalk to the orange exterior of a newly-carved jack o’ lantern. Rough-barked ponderosa pines lined the draws at random intervals, towering over the twisted trunks of Rocky Mountain junipers.

Two centuries before our excursion into this badlands wilderness, the ebony eyes of elk and the restless oversized ears of mule deer marked the passage of the heavily laden boat as the Lewis and Clark expedition labored up the river. Still abundant in the breaks, we spied a herd of some thirty elk tiptoeing among the junipers on the far side of a broad ravine. Mincing to the south brink of the butte, we jumped a trio of mule deer does, their hooves sinking deeply into the eroded sandstone as they bounded into a stand of pines in the bottom of a ravine. Although we spotted their scat and tracks, the “rock mountain sheep” encountered by the captains remained absent from the landscape.

As predicted, temperatures rose to unseasonable levels from the chilly air of dawn. Heat waves began an undulating waltz across the breaks, making it difficult to glass much farther than a mile. Cresting yet another of the endless abutments of sandstone above the river, we paused for a breather. Micah reached for his water bottle as I glassed a yonder butte previously hidden from our sight. Near a stand of ponderosas, the bodies of eight animals appeared in a pasture of bleached grass. The thermal interference made it impossible to identify them with certainty, but they looked like sheep. Intimately acquainted with the gait, posture and habits of mule deer from a 40-year acquaintance, I knew they weren’t deer. Notifying my son of their presence, his response was instantaneous.

After an hour of hiking, we cut the distance to less than half, close enough to easily discern the stubby horns of the ewe-band and their large pale rumps with trademark white “pants” descending on the inside of their legs. Knowing rams are seldom among the females at this time of year but may be frequenting nearby habitat, we decided to cross a broad, deep ravine to reach a finger ridge descending from the ewes’ position. It was a grueling hike, dry, gritty and steep. As we reached the ridgetop I turned to assess my hunter.

“How are you feeling?” I asked.

“Fine.”

Lying across a broad platform of sandstone, we had a slightly higher angle from which to view the ram. However, even with the extra elevation, all we saw were its horns and forehead. After several moments, it turned its neck slightly, revealing heavily-broomed headgear, easily a legal, three-quarter curl ram.

In hushed tones we engaged in a session of question-and-answer. The discussion included the merits of the ram, the potential for finding another, the fact that a storm front was moving in the following evening and the amount of time we might need to wait before the sheep stood to offer a shot.

“Should I take it, dad?” The question came as much from the pair of intense coal eyes as the mouth which formed the words.

“That’s up to you,” I replied, determined to keep the hunt about the youth, not a hunting parent’s unrealized aspirations in relation to such a treasured tag.

“Do you think we’ll see more sheep?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Then I think we should look for a bigger one and come back here if we don’t find it.”

“If he moves, he might not be here when we come back,” I suggested.

“That’s okay.”

“The other one was bigger, right?”

I nodded, noticing the mid-afternoon sun seemed lower than it was just moments before. A three-mile hike led back to camp. As we turned to go, I took one last, wistful look at the younger ram with the wide, unblemished horns, fantasizing a sheep tag of my own in a couple of years with the beauty properly grown-up.

Less than a mile into the return route to camp, we spotted yet another ram. Bedded in an opening about a half-mile away, its horns appeared slightly longer than the previous rams’ and were a bit heavier, bearing the chips and scars of rut-time clashes with rivals of its own kind.

“I think I should try for that one,” concluded Micah.

We snuck carefully in the most logical direction of its departure. About the time we reached its abandoned bed, the sheep exploded from a pocket 50 yards ahead, obviously spooked by our scent. It trotted over a rise. We jogged in pursuit. It showed itself within shooting distance on the far side of a gulch, but by the time Micah planted his posterior on the hard hearth for a shot, it slipped into a stand of junipers.

For the next two hours we followed the wraith-like ram over pointed hill and dusty dale, up eroded gullies and across knife-edged ridges, sometimes by supreme effort catching a glimpse of its departing backside, never

“If we can make the next 300 yards in less than two minutes, you’ll get your shot,” I urged.

We reached the spot in less than the appointed time. Lying prone, Micah bolted a cartridge into the chamber just as the ram appeared in an opening in a copse of scattered pines. It stopped. On cue, the boy fired, but the shot flew over the ram’s shoulder. It bolted again, then resumed its race-walk pace. In the falling light it vanished into the shadowed evergreens.

Too tired to follow, knowing we’d not overtake it again before darkness, I sensed Micah’s dejection. There wasn’t anything to say, so I glassed a faraway hillside in the direction of the departed ram. To my surprise, I again found the sheep in my binocular, not walking, but grazing placidly on the canted pasture. Handing Micah the binocular, I pointed out the ram’s location.

“If we’re over there at daylight, we’ll have a chance of finding him.”

“A good chance or a little chance?” asked the subdued voice beside me.

“A really good chance,” I replied with conviction.

Marking the position of a flat-topped butte jutting above the grazing sheep, we began the hike back to camp. It was arduous, but immensely gratifying to be out in an untamed world of sandstone and sagebrush with an enclave of shiny stars applauding from the black balcony overhead. Before dawn the next morning, the same celestial celebrants marked our passage back toward the abode of the tantalizing ram.

It wasn’t in the previous evening’s pasture, but we found the ram about a mile beyond it. Unfortunately, the sheep had already won the game of “I spy.” In a classic case of déjà vu, it trotted over a rise and disappeared. Four ravines and five ridges later, Micah again brought his crosshairs to bear on the ram. The first shot flew wide but the second connected. A third 140-grain bullet from Micah’s .260 Remington hit the sheep’s ribcage, and it piled up at the bottom of a gully. When we reached the fallen ovis canadensis, there was much smiling but we were far too tired for whooping and hollering.

After some quick celebratory photos, I boned and caped the ram. Three miles from camp with a north wind blowing, it seemed smarter to ferry the animal in a single trip rather than roll the dice with the weather. We managed to secure all the boned meat, the head and cape and our sparse kit of gear into our two backpacks, each laden with twice the weight we’d normally choose to carry.

Driving toward a rendezvous with a game warden to complete a mandatory check-in of the sheep with a sleeping youth on the seat beside me, I concluded that although it was luck that bestowed Micah his tag, he earned his ram through intense, honest effort. The warden voiced a similar opinion. After quizzing us about the location of the kill, the details of the hunt and aging the ram at seven years, he shook the boy’s hand. “That’s a fine sheep, son, and you should be proud of the way you got the job done.”