Observations

All Encompassing Preference

column By: Lee J. Hoots | January, 20

More than 10 years ago a non-hunting acquaintance in California once asked what big-game animal I preferred to hunt. It seemed to be an odd question from someone I hardly knew, and a question for which there probably was/is no definitive answer. Then he put it another way: “If you could only hunt one big-game animal in North America for the rest of your life, what would it be?”

Figuring the questioning might lead somewhere I didn’t want it to go, and being caught up in the moment, I provided an answer to that more narrowly-pointed query, hoping it would be a somewhat easy way to end the conversation, or at least change the subject. “If forced to choose just one option, it would be the American pronghorn, hands down, no questions asked,” was the somewhat rash response.

Having pondered that question off and on over time, I’ve decided the subject is far more complex because at first it did not include (but should have) a wide range of other North American game. However, Rocky Mountain goats, moose, musk ox, caribou and the various native wild sheep should probably be removed from the equation, as would the grizzly and brown bear. This is due largely to the fact that hunting these critters unfortunately entails exorbitant fees, and money cuts out most of us common woodsmen.

This in turn narrows the topic to the typical deer subspecies and perhaps the black bear. Furthermore, it’s not certain black bears should be considered here because most big-game hunters pursue the various deer more than any other game except perhaps pronghorn, so it makes sense to focus on ungulates here.

It is my personal perception that Rocky Mountain elk most often provide the most physically (and sometimes mentally) challenging hunting of all. On the flip side, elk hunting comes with its perks, especially when a rifleman or bow hunter can get a tag during the bugle season before the woods have withered and daytime temperatures plummet.

Even in the best areas, however, elk hunting is usually never easy and can be downright frustrating. I once stumbled around for several days in prime habitat in New Mexico on public land where every morning bulls were bugling as the sun came up. As quietly as possible, my buddy (hunting a different part of the unit) and I hustled to find the vocal bulls with no luck. While sharing each day’s events back at camp at night, our stories were similarly frustrating. The herds were active for an hour or so but eventually moved off onto private land to spend their time away from hunting pressure. Each time either of us thought we were getting close, the bulls quit sounding off and drifted toward who knows where.

A change of plans became necessary. With two days left, we were granted permission to cross private ground in order to access a chunk of public land. Both of us, hunting not too far apart, shot excellent bulls with little time to spare.

Prior to that New Mexico outing, a landowner friend and I struggled to get close to a bull in Colorado. It rained nearly every hour of each day, which can be troublesome when carrying a .50-caliber sidelock muzzleloader loaded with loose Pyrodex that soaks up moisture rather quickly. There were few big bulls around at the time, but it was what it was. The bulls showed little sign of rutting behavior with the exception of occasional bugling, but that’s how it goes sometimes. I did my best to keep moisture out of the lock and barrel, but it didn’t seem to help. Clearing and cleaning the rifle twice during the day and each night proved to be a chore.

Then there’s the mule deer. It should be said that as a youngster I cut my teeth bow hunting California bucks, a somewhat smaller subspecies on par with the blacktail that is as difficult to get an arrow into as the big Rocky Mountain deer found in Colorado, Montana, Utah and other western states, or the desert deer of the Southwest. As a kid, I shot my first doe muleys with a rifle in the great state of Montana. In the past several years the same state (as well as Utah) has provided a couple of better than average bucks – shot with a rifle – that hang on the wall in my humble reloading room/library. Glancing at them now, it’s certain that mule deer hunting could never be overlooked or given up.

I would be happy hunting the dainty Coues’ buck every year if a tag could be obtained (see Successful Hunter No. 102, November 2019). It’s cousin, the common Virginia white-tailed buck provokes mixed feelings. Having hunted in several states from Wyoming down to Texas and clear across to Georgia and Mississippi, I find it somewhat less interesting hunting them from a blind and have just about sworn off tree stands altogether. This might sound odd given the fact that I’ve shot several nice bucks from a blind and find it acceptable when other hunters do the same. There are parts of the country where few whitetails would ever be seen if it were not for the use of tree stands, and ground blinds work nearly as well. They are just not for everyone, including this westerner.

Fortunately, whitetails thrive in several states in the West and Midwest where they can be hunted on foot. Wyoming is a key example. Two very nice whitetail bucks have been shot there after spotting them from a distance and making a careful stalk. They aren’t quite as big as those I’ve shot in Kentucky or Oklahoma from a blind or stand, but there’s nothing quite like sneaking up on a mature whitetail, perhaps the smartest deer known to man. Nope, there’s no way I could give up on hunting whitetails either, so long as my boots are on the ground.

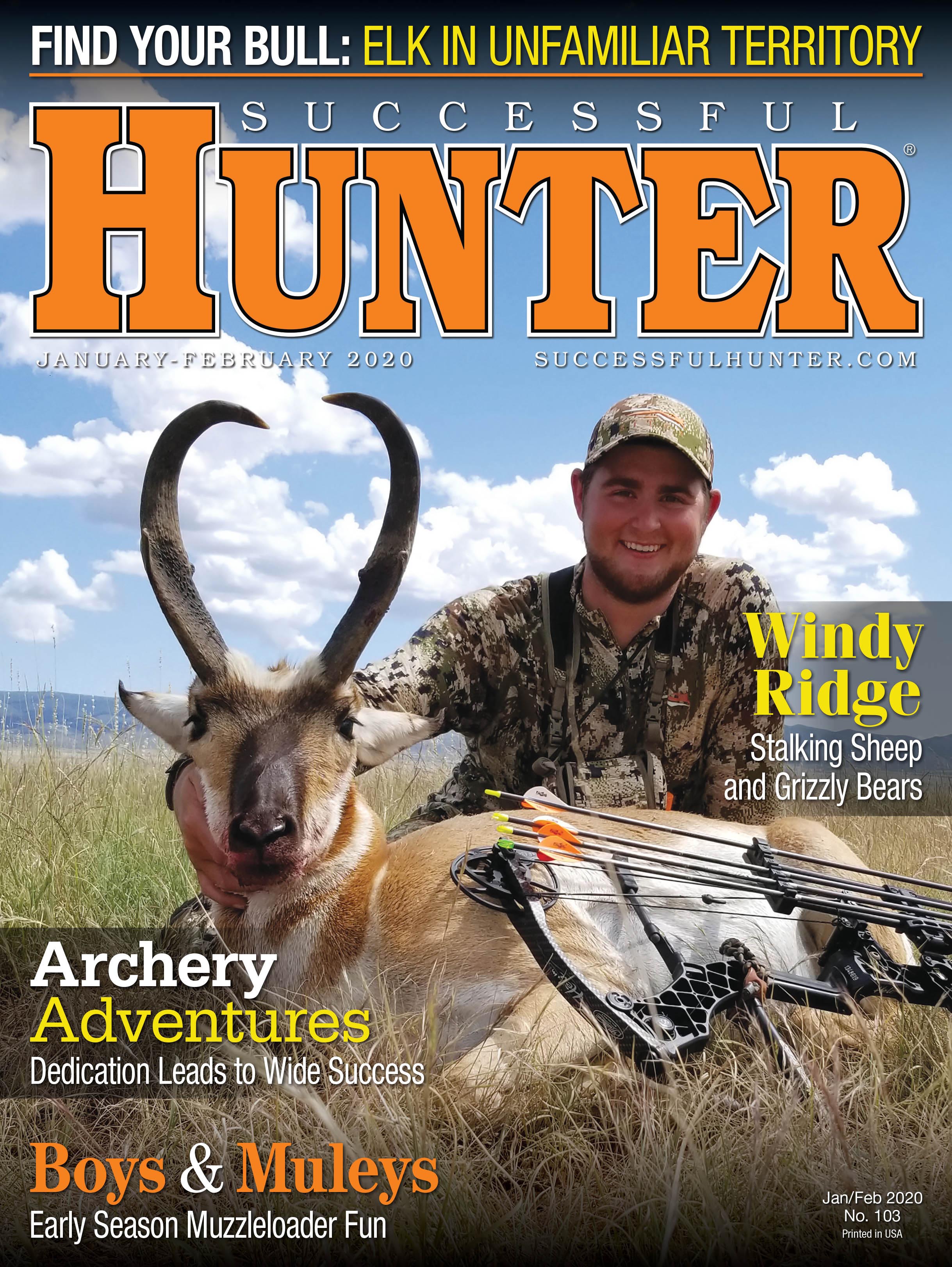

The sharp-eyed pronghorn has been intentionally left for last because, truth to tell, it’s colored like the high desert habitat that I also enjoy. Found throughout the West, pronghorns have long been my favorite game animal to hunt since shooting my first with a rifle in Montana at a young age. In spite of shooting my first in the Treasure State as a kid, a friend who has carried a rifle far and wide across Montana (and still does) finds my preference for Wyoming, well, somewhat perplexing.

Trying to put a fine point on why would be as useless and silly as picking one specific big-game animal I would be happy to hunt the rest of my life while ignoring all others. Like the query proffered so long ago by a nonhunter, it makes no sense at all. Every species has its challenges, and all game should be enjoyed and valued.